The Need for Diversity in the English Curriculum

October 23, 2020

The Black Lives Matter movement, focused heavily on addressing institutionalized racism in the American police system and popularized by the phrases “ACAB” and “Defund the police”, has been in the public eye since late May following the death of George Floyd and the nationwide manifestations that followed; yet the lesser-acknowledged intention of this crusade, equal representation in the media, workplace, and political platforms, has been pushed forward by schoolteachers seeking to diversify the English curriculum. Grassroots organizations such as ‘We Need Diverse Books’ and ‘DisruptTexts’ advocate for essential changes in the literature pedagogy and publishing practices in order to achieve an educational program that reflects the physical and cultural natures of all students.

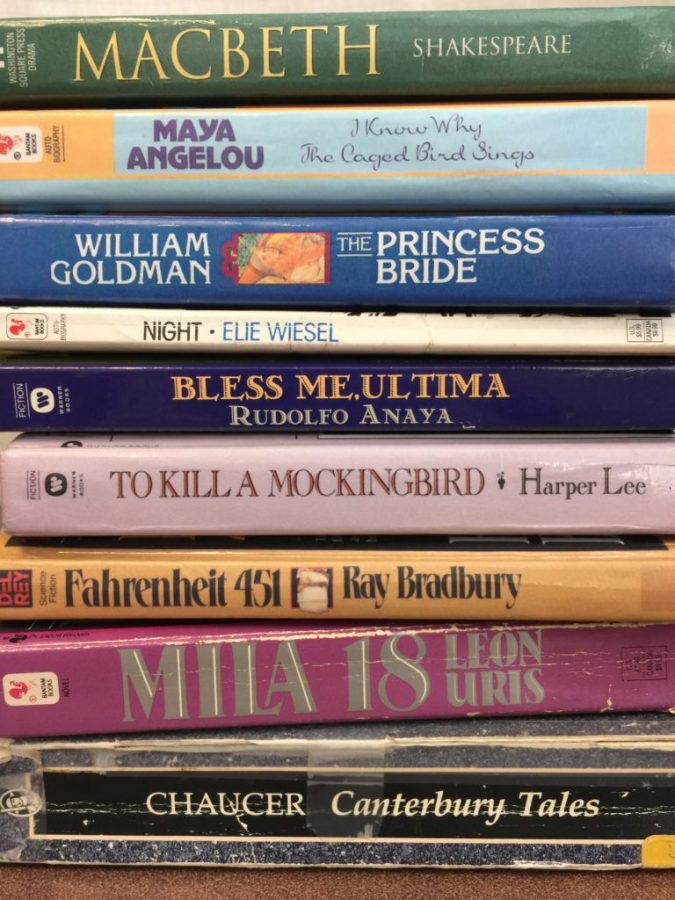

The argument of unequal representation in children’s books and classic literature is not relatively recent, yet the continually-evolving identity of the United States from a standard population of middle class, white, cisgender males has ensured that forms of media written by and promoting protagonists that conform to this description are no longer acceptable as the sole component of school curriculums. A 1965 Saturday Review article, written by Nancy Larrick and titled “The All-White World of Children’s Books”, spoke of the phenomenon occurring in classrooms around the nation: children of color were learning from books that completely omitted them; “Perspectives: Choosing and Using Books for the Classroom”, a 1990 Rudine Sims Bishop publication, addressed the importance of diversified media representation to change the global attitude and intolerance towards difference. In the past 25 years, as this dispute has been continuously buried under issues deemed more urgent, the American student population has grown to be 50% non-white and provided with a narrow selection of children’s literature, 13% of which houses multicultural content and 7% of which are written by people of color. The scrutiny of classic, accepted texts – such as Boston librarian Liz Phipps Soeiro’s rejection of First Lady Melania Trump’s 2017 donation of Dr. Seuss books to her school’s collection – is growing more and more common as online modules and workshops create a growing understanding among teachers concerning conversations about diversity and race. These conversations have grown to encompass the racialized language in “Huckleberry Finn” and “To Kill a Mockingbird”, the treatment of and attitude towards disabilities in “Of Mice and Men”, and the sexual content in “Romeo and Juliet”, although contemporary texts such as “The Hate U Give”, a novel being introduced to countless schools across the country, are contradictory due to anti-cop sentiments and lack of censorship around profanity and drug use. Of course, authors like Fitzgerald, Salinger, and Shakespeare are indubitably staples in every learning environment and should not be disregarded due simply to diversity or their lack thereof, as their works transcend generations and touch upon human values, yet as the curriculum fills up with classics the space for modern texts narrows. While designing a curriculum, teachers and administrators must consider books that are a crucial part of our cultural and literary history as well as those that widen the mindsets of students and provide various lenses through which to observe the world. The argument is disputable from both sides: removing “The Great Gatsby” and “Great Expectations” from the classroom library is unheard of and considered a failure to prepare the student for cultural conversation, yet allowing a student of minority lineage to grow up surrounded by books written by and representing solely the white population is a detriment to the child psyche and a step away from equality. It also raises the question of the true purpose of teaching literature; is it simply to provide the interpretation, vocabulary, and cohesion skills necessary for higher education, or to equip students with books that act as both mirrors and windows in order to celebrate our similarities and differences?