How the War on Drugs Is Failing Black Americans

May 24, 2021

This is an opinion article piece. Nate SCoenbrodt is a student at Mendham. All opinions expressed in the following editorial are his own and do not necessarily reflect the views of The Patriot.

“The Nixon campaign in 1968, and the Nixon White House after that, had two enemies: the antiwar left and Black people.”

“We knew we couldn’t make it illegal to be either against the war or black, but by getting the public to associate the hippies with marijuana and blacks with heroin, and then criminalizing both heavily, we could disrupt those communities. We could arrest their leaders, raid their homes, break up their meetings, and vilify them night after night on the evening news. Did we know we were lying about the drugs? Of course we did.”

The quotes above were found in a 1994 magazine report interview with former Nixon administration Domestic Policy Chief John Ehrlichman. On June 17th, 1971, President Richard Nixon declared a “war on drugs; stating that narcotic use was the United States’ greatest issue, he promised that a bundle of resources would be directed at fixing the crisis. Immediately after Nixon’s announcement, the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) was founded. While originally given 1,470 agents and a budget of less than $75 million, today the DEA has nearly 10,000 agents and a budget of $2.1 billion. America does have an ongoing narcotics issue that needs to be properly addressed, but the federal government’s approach has only worsened its state. Here’s how.

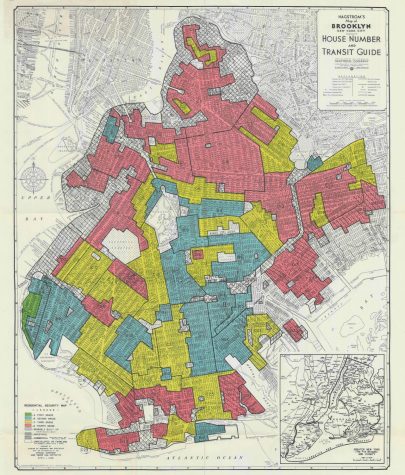

The systematic oppression of Black Americans is one that began with the slave trade in 1619 but continues into today. Once slavery was abolished following the Civil War, Black Codes and sharecropping constrained the societal integration of freedmen. Black Codes were laws passed in the Reconstruction-era South that separated freedmen from entering city borders, limited property ownership, denied wage increases, and subjected those who broke work contracts to beatings, arrest, and forced labor.  This tactic of systematic discrimination was eventually disbanded, but its sentiments continued to plague the country as Jim Crow and legal segregation further prevented Blacks from wholly progressing in the United States. Segregation, which ended only 57 years ago, separated Black families from job opportunities, access to education, and a true sense of protection. The general state of Black Americans worsened during FDR’s New Deal in 1933 under the Homeowners Refinancing Act. From this, redlining began– the process where government officials mapped out populated areas and decided, based on its financial success, which communities should receive federal banking assistance to recover from the Great Depression. Expectedly, the Black Americans who had been excluded from opportunity and marginalized by the government for decades were poorer than White Americans and were therefore denied assistance. Deemed “hazardous”, these Black communities would eventually mold into what we know today as “ghettos”.

This tactic of systematic discrimination was eventually disbanded, but its sentiments continued to plague the country as Jim Crow and legal segregation further prevented Blacks from wholly progressing in the United States. Segregation, which ended only 57 years ago, separated Black families from job opportunities, access to education, and a true sense of protection. The general state of Black Americans worsened during FDR’s New Deal in 1933 under the Homeowners Refinancing Act. From this, redlining began– the process where government officials mapped out populated areas and decided, based on its financial success, which communities should receive federal banking assistance to recover from the Great Depression. Expectedly, the Black Americans who had been excluded from opportunity and marginalized by the government for decades were poorer than White Americans and were therefore denied assistance. Deemed “hazardous”, these Black communities would eventually mold into what we know today as “ghettos”.

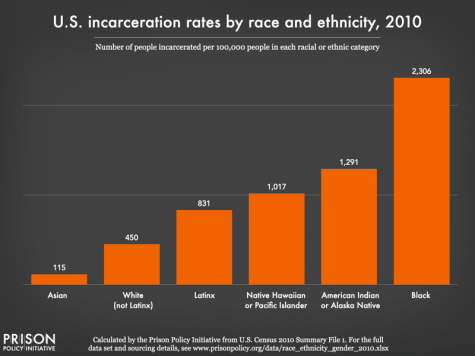

This brings us back to 1971 and the War on Drugs. Nixon’s initial promises to target the narcotic-using population quickly shifted to target the poorest of the poor and the easiest to criminalize: Black Americans. The War on Drugs was kick-started with widespread over-policing, in which police officers heavily patrolled minority neighborhoods. Despite consuming drugs at similar rates, Black Americans began to be arrested at far greater rates than white Americans. This pattern even stands true today; despite roughly equal usage rates, Blacks are nearly four times more likely than whites to be arrested for marijuana. Blacks are also easier to target because of their financial disadvantage, as limited access to satisfactory legal representation makes them less difficult to prosecute. Thus, high rates of Black crime and arrest are not driven by inherent-racial desires to commit crime or efforts to make a statement to political opposition, but instead consequences of racially targeting laws.

The War on Drugs was worsened in 1986 with the Regan administration’s Anti-Drug Abuse Act and the introduction of mandatory minimums, criminal sentences which courts must give to a person convicted of a certain crime. Sentencing disparities were highlighted in how the act dealt with crack vs. powder cocaine. Crack cocaine, the drug Blacks used more because of its easy accessibility and low cost, required a five-year sentence for possession of five grams. Powder cocaine, the drug used by white elites and that cost exponentially more money to produce and acquire, required a five-year sentence for possession of five hundred grams. Even though the use of mandatory minimums has recently declined, little has done to address the deeper, systematic issues regarding race in our country.

Through legal ostracism, over-policing, and mandatory minimums, the modern system of mass incarceration was created. Today, many Black Americans, born into poverty as a result of centuries-long displacement and separation from opportunity, look to crime as a means to get by. Also, one in four Black children has a parent who is or had been incarcerated. It’s easy to envision what growing up in a ghetto, surrounded by crime, separated from education, and without access to parental guidance can do to an impressionable kid. Especially with recent cuts in social programs and increasing attention to police brutality, Black Americans are reminded daily of their treatment as second-class citizens.

Through legal ostracism, over-policing, and mandatory minimums, the modern system of mass incarceration was created. Today, many Black Americans, born into poverty as a result of centuries-long displacement and separation from opportunity, look to crime as a means to get by. Also, one in four Black children has a parent who is or had been incarcerated. It’s easy to envision what growing up in a ghetto, surrounded by crime, separated from education, and without access to parental guidance can do to an impressionable kid. Especially with recent cuts in social programs and increasing attention to police brutality, Black Americans are reminded daily of their treatment as second-class citizens.

So the next time you hear someone complain about the Black crime rate, affirmative action, or recent callings for social justice, point out the hypocrisy of our country being called the “land of the free” while having the highest incarceration rate in the world, and start the uncomfortable conversation.