Sustainability 101: Class Is In Session

The answer to the problem of climate change may lie in US classrooms.

December 12, 2018

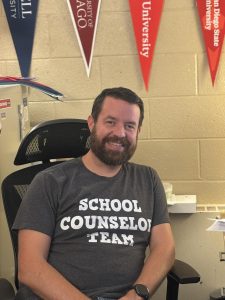

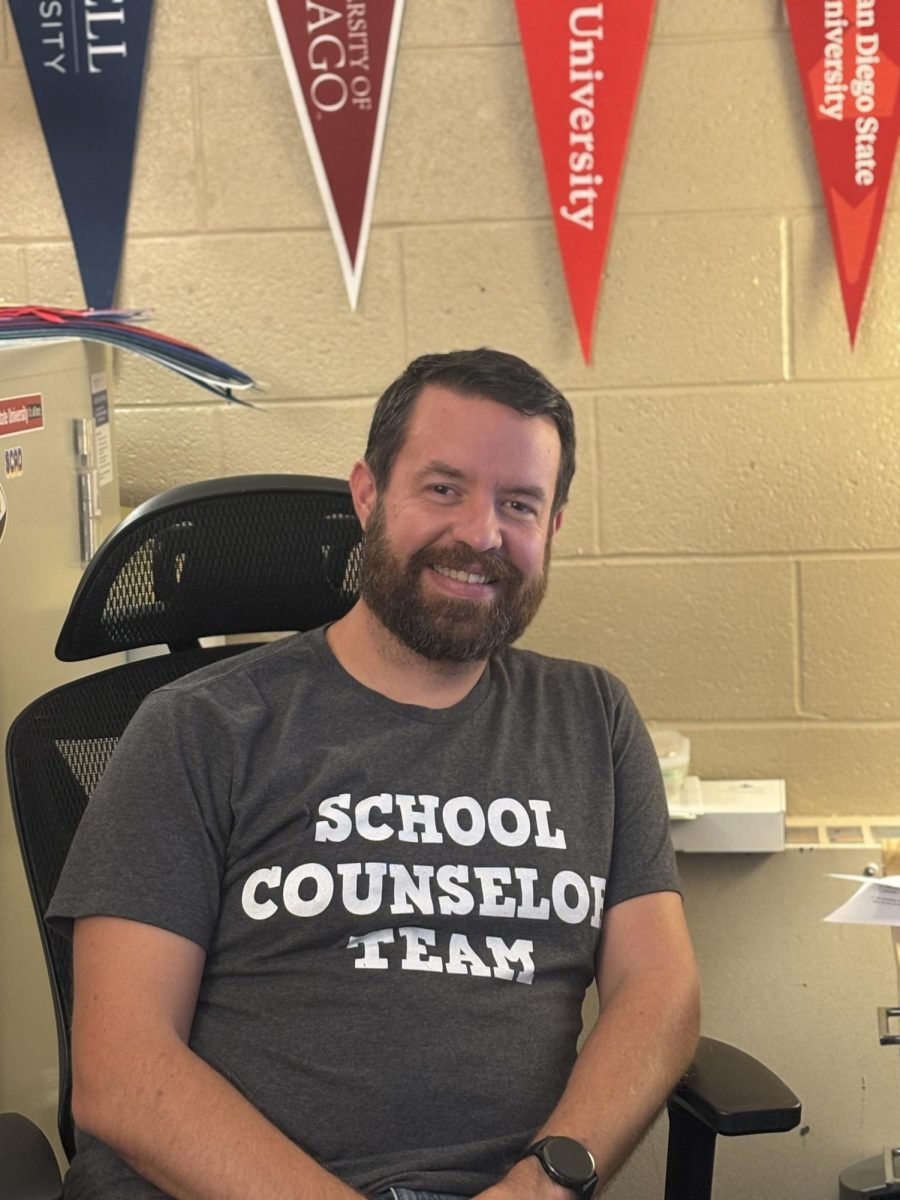

“I like to think of sustainability as an octopus,” says Liz Cutler, Sustainability Coordinator and English teacher at Princeton Day School. “It’s got eight arms, sustainability has a lot of arms, it doesn’t matter which you shake hand with – you’re going to get to sustainability. You could start with food, with composting, with reducing waste, you could start with water fountains, and each one will lead to the next project and the next.”

The recent–and very troubling–UN Climate Report stresses the imminent danger of global warming and environmental degradation. The new report warns that we have twelve years to mitigate the effects of climate change, a deadline that is fast approaching. For the more than 56 million elementary and high school students, that means we’ll be graduating into a world of climate disasters. So, Cutler says, it’s important for schools, themselves, to make sustainability a priority. But are schools receptive to sustainability? It depends where you go.

When Liz Cutler arrived at the Princeton Day School (PDS) as an English teacher 35 years ago, she started an Environmental Action Club for the students, one of the oldest in the country. PDS is a private school located in Princeton, NJ. Cutler’s club was meant to involve her students in sustainability, the environment, and the community. From the beginning, her students were extremely active.

In the earlier days of the club, a swath of land neighboring PDS’s campus was slated to be sold to a housing development. To preserve the land, the students in the Environmental Action Club went to the community. They wrote a flurry of letters to the editors of local newspapers, organized a walk for open space, and ultimately raised $50,000 to purchase the eleven-acre plot of land. Today, it is home to a wildflower meadow, school garden, and compost area.

Cutler explains, “It just takes willpower. It’s not about money. So lot’s of people say, ‘oh you go to a private school, you have all this money.’ Well, I can tell you our garden costs $600 which we made by selling coffee cups that our ceramic students made in the ceramics studio. Everything else was either donated or was labor by volunteers. We built that garden in 8 hours with 200 volunteers.” The garden is an expansive plot of land located near the lower school building. In raised beds, students, staff, and parents at PDS grow everything from corn to wildflowers. Students can also have class in the garden, bringing education outdoors.

The families of PDS care about the future of the environment, but how did it get that way? Cutler’s strategy was to appeal to the social hierarchy of the school to make the club and its message popular with the students. “You’ve got to make it cool,” she explains. “The question is, so what makes something cool? Field trips, food, a couple of cool kids, so when we started this, it wasn’t cool. I’m not sure its cool now, but we have 30 kids show up every single Friday for lunch, that’s a lot.”

Cutler’s dedication to sustainability has shaped the curriculum at PDS. Students of all levels have classes outside and in the garden, and select high school students can join a program called Climate and Energy Scholars, which is a partnership with Princeton University. Every month, graduate students from Princeton come and meet with the Energy and Climate Scholars to teach them about climate change from a variety of different perspectives based on the research that they are doing at the University. Students as young as three or four are encouraged to take an active role in sustainability and activity increases with age.

PDS’s focus on the environment has an effect on students’ lives long after they leave PDS. Cutler explains, “Obama’s energy advisor was a graduate from my club, you know, those seeds go with them in their personal lives, their professional lives, not all but many. Some of the Energy and Climate Scholars have chosen to do their summer internships at NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association) or some other climate change-related place.” PDS’s program has shaped students’ professional lives and aspirations, a testament to the success of the program and the influence of education. But PDS isn’t the only school that prioritizes sustainability.

In fact, in New York City, every school is required to appoint a sustainability coordinator, typically a teacher, but sometimes an administrator, who is tasked with managing their school’s involvement in the program. They act as a point person for GrowNYC and the school. To develop a successful complex sustainability infrastructure, schools can turn to organizations like GrowNYC. A citywide organization called GrowNYC provides helps the school sustainability coordinators to educate students on sustainability and the environment and to build student leadership around sustainability.

A school’s level of commitment to the program is purely up to them: some teachers run extracurricular programs after school or support green teams during a lunch or prep period. Students create their own environmental clubs or take on sustainability activities through student government organizations. “Each school is like its own ecosystem, some schools have sustainability as a priority more than others,” says Jen Ugolino, a coordinator at GrowNYC. “Some students might be talking about sustainability throughout all of their different classes, whereas others might be learning about sustainability just in an environmental science class.”

Though schools have varying levels of involvement in GrowNYC’s programs based on interest, the important thing is that the infrastructure is available. GrowNYC is looking to the future, hoping that it will be greener. Ugolino confesses that she’d like to see students, and people in general, across the city, participating in “some very simple, easy to do actions to become more sustainable in their daily lives, for instance, all residents, students, teachers should be able to take part in things like gardening, composting, recycling, reusing.”

In schools without support systems like PDS’s or NYC’s GrowNYC program, making a sustainable transition can seem impossible. Bruce Taterka, an Environmental Science teacher at West Morris Mendham High School in New Jersey complains of an unaccepting and close-minded school community. With his Environmental Club, students built a school garden, ran an e-waste drive, and organized campus cleanups, among other green activities. However, he took on a disproportionate amount of the responsibility, and this year he stepped down, exhausted by the rigor of his work and lack of interest from the student body. Taterka says, “I’ve been very frustrated here with the lack of sustainability efforts,” and laments the difference between PDS and WMMHS, saying, “they have a sustainability coordinator, the administration is behind it, the community is behind it. It’s a priority. It’s part of the culture there. That doesn’t exist here at all. We’ve tried for years just to get recycling improved here. It’s very hard to do things when there’s not support.”

Despite the slow and sometimes frustrating progress at schools like West Morris, sustainability in schools around the country is on the rise: in 2017 the number of LEED Certified schools hit over 2,000, according to the US Green Building Council. Most of the projected growth is expected to come from public schools. LEED buildings are sustainable, using fewer resources and often generate energy through solar panels. Environmental programs, clubs, gardens, compost, and recycling, are becoming ubiquitous in American schools, often driven by students and teachers.

For whatever level of enthusiasm a student body has, there is some change, large or small, that can make a school more environmentally friendly. From green buildings and solar panels to relabelling trash cans and making recycling a priority, change in schools is possible on every level. Not only will these programs reshape a school’s relationship with sustainability, but they also have the power to fundamentally change the way students view the environment.