Despite What Some Say, New Jersey’s Governor Race Is Competitive

The state voted for the Democratic candidate in 2020 by a margin of 725,061 votes. Can a Republican flip the state in Tuesday’s governor race?

November 1, 2021

For many New Jerseyans, the possibility that their state might flip into the Republican column in November’s gubernatorial race is wishful thinking. In last November’s presidential contest Joe Biden won the state by a margin of 15.9%, and a Republican presidential candidate has not won the state since George H.W. Bush captured it in his 1988 landslide. The State Assembly and State Senate have been controlled by Democrats since 2004, and Phil Murphy, the Democrat incumbent governor, won his 2017 election bid by an impressive 14.1% with polls now favoring him in his upcoming reelection. History, as well as experience with that blue tide that runs deep in urban New Jersey, points clearly in the direction of Phil Murphy for November’s victor, and three major race rating outlets have named Murphy the probable winner. Yet, despite the polls, the deep blue politics of New Jersey, and the massive bastions of Democratic voters in cities like Newark and Jersey City, the race is closer than it seems.

Anyone who remembers Biden’s massive New Jersey margin last November may be convinced the state cannot flip, but presidential election contests in New Jersey are a different species than governor races and therefore are unreliable predictors of gubernatorial results. In presidential contests in New Jersey, parties seem to dominate for alternating periods of many years. Democrats reigned in the 1930s and 1940s, while Republicans had a massive win rate in the forty years from 1948 to 1988, only for the state to flip back with New Jersey falling into the Democratic column in every presidential election since 1992. Yet New Jersey’s governor races do not follow this pattern, instead flipping back and forth in much shorter, rapid cycles of partisan exchange. The governorship has changed parties 8 times since 1965 with no party presiding in Trenton for more than two consecutive terms at a time. In light of this historical trend, the idea of the state flipping is slightly more conceivable.

The statement that Murphy leads in opinion polls is true, but this advantage is not as substantial as Murphy’s margin was in 2017 and nowhere near what Christie attained in 2013 in his reelection endeavor. Polls have told a story of slowly waning support for Murphy through the 2021 election cycle, starting with a polling lead in the 20% to 30% range in June, dropping to between 10% and 20% by late September with a few polls, namely one taken by National Research Inc., beginning to suggest a close margin between the candidates. This decrease in Murphy’s edge continued the rest of the way through September and into October, with more polls, including ones by Stockton University, Schoen Cooperman Research, and Fairleigh Dickinson University, reporting a lead of 9% which is less than his official margin in 2017 and even farther from where he was positioned a few months ago. An immense surprise arrived when one poll by Emerson College reported a lead of only 6% for Murphy with 7% undecided, and of that uncertain group 59% leaned toward Ciattarelli compared to 41% leaning toward Murphy. If these voters are assumed to vote in the direction in which they lean, the lead that Murphy holds over Ciattarelli in this poll is just 4%. While predicting the future based on current trends can be treacherous, this months-long decrease in Murphy’s lead from over 20% to single digits means that the race has the potential to be tight on election day.

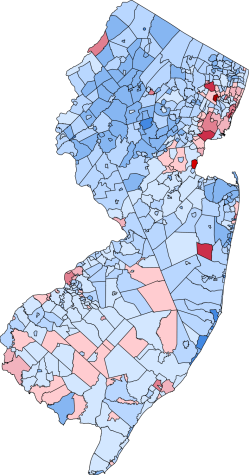

What has happened in the last five years in New Jersey races tells a compelling story about the state. 2016 Democratic presidential candidate Hillary Clinton won the state against Donald Trump in a 55-41 margin, with many of its counties shifting to the right compared to 2012 with the notable exceptions of middle-class, suburban Morris, Somerset, and Hunterdon counties. This suburban shift to the left was a nationwide phenomenon in the 2016 presidential election, occurring also in Atlanta, Washington D.C., Chicago, and Dallas suburbs. This shift reversed somewhat in the 2017 governor election where Trump was not on the ballot, with northern New Jersey suburbs shifting rightward toward their usual political standings. Yet 2020 came around and, with Trump on the ballot again, Morris, Hunterdon, Somerset, Sussex, and Bergen counties moved left, all of which are suburban counties with an extensive middle class. For the first time since 1964, a Democratic presidential candidate won Morris County, and for the first time in decades, a Republican won Hunterdon County by less than 5%. Somerset County’s Bernardsville, a middle-class town in the heartland of northern New Jersey, moved to the left by 18% compared to 2016, one of the largest leftward shifts in the state. Trump seemed to repel the suburban middle class, but where he gained strength in 2020 was inner-city areas such as Newark, Paterson, Elizabeth, and Camden, a pattern that existed in other urban areas across the country and that was likely due to certain minority groups drifting rightward. With Trump not on the ballot in New Jersey in 2021, and in light of how Ciattarelli has wished to avoid the topic of whether he has ties to Trump, bringing voters in northern suburbs back to the right is both a goal and a viable possibility for November’s race. Although Murphy’s attempt to connect Ciattarelli to Trump may hurt the extent to which this happens, if a large suburban shift to the right occurs while Ciattarelli also holds on to the gains Trump made in urban areas, there is a basis to wonder if the state may be competitive this year.

Another factor behind New Jersey’s gubernatorial outcomes may be the party and popularity of the sitting president, with voters tending to choose the opposite party of the current president if their approval is low. In 2005, when a Democratic candidate won the governorship, a Republican president was in office and his disapproval rating was greater than his approval rating. In 2009 at the time of the New Jersey governor race, Democratic President Obama’s approval rating was slightly higher than his disapproval rating even though a Republican, Chris Christie, won, but this may have been due to incumbent Democrat Jon Corzine’s extreme unpopularity. In November 2013 Obama’s disapproval rating was higher than his approval rating and Christie, of the opposite party, won the governor race. In 2017, Republican Trump’s disapproval rating was higher than his approval rating and Democrat Phil Murphy, of the opposite party, won the governor race, and now, in 2021, Biden’s approval rating has dropped significantly in recent months and his disapproval exceeds his approval. The question is whether or not the sitting president’s unpopularity can coerce New Jerseyans to vote for the opposite party of the president, which recent New Jersey history may indicate.

Murphy’s polling numbers compared to his margin in 2017 and Biden’s in 2020 are weak, showing an apparent shift to the right in the electorate that is not found only in New Jersey. This shift is mirrored in Virginia, a state that Biden won by more than 10% where the two gubernatorial candidates are currently neck-and-neck in polls. In consideration of how 2016, 2018, and 2020 polls commonly overestimated Democratic margins in presidential, Senate, and congressional races, the Republicans in the Virginia and New Jersey governor races may be more attractively positioned than where they stand presently.

At the end of the day, New Jersey is a blue state and Murphy holds the lead, but its upcoming gubernatorial race is more competitive than commonly believed and there is a possibility that the state will fall into the Republican column on November 2nd in a stunning upset.